I guess we’ve all had the experience of knowing something but somehow not being able to recall it.

Maybe it’s someone’s name. Or maybe where you put your car keys. Sometimes it may be what you heard in a sermon a few hours ago.

There are reasons why our brains sometimes fail us in this way, and they are relevant to how churches work.

Read on to find out why.

Getting information in

Our brains can store massive amounts of information. But we’ve got to get information into memory, and then be able to get it out when we need it.

These processes aren’t as simple as you might think.

Too much information!

Our senses are bombarded with all sorts of inputs.

We may be listening to our friend telling us something, but in the background there may be the sound of traffic, a TV in the next room or the rain on the roof.

While we’re watching a football game at the park, our focus will be on the players and the ball, but our eyes are also receiving light from the grass, and the sky and the crowd on the other side of the pitch.

We may also be conscious of the smell of car exhaust or our feet getting cold.

If our brains tried to process all this information, they would be overwhelmed. So they filter a lot of it out. We hear or see it, but don’t really notice it all and we certainly don’t remember it all.

How does this work?

Sensory memory

Input from our senses goes into sensory memory, where it typically only stays for less than a second. The brain decides what inputs we are paying attention to and filters out the rest and they are lost.

Short term memory

Inputs which get through the filters go into short term memory, also known as working memory. Here the brain decides what to do with this information. If it is important, it will be passed into long term memory, otherwise it will be forgotten.

But there are limitations of the capacity of short term memory.

Items only stay in short term memory up to 30 seconds. If they haven’t been processed by then, they will be forgotten. We can sometimes prevent this loss by repeating the information, for example, saying a phone number out loud until we can write it down.

Only about 6-8 pieces of information can be held in short term memory at one time. If extra information arrives it will either be lost, or else it will replace information already there. If we want to retain information, we should avoid being bombarded with facts. It is also possible to to repeat information so it is joined or “chunked” together and several pieces of information become just a single piece, thus allowing space for further memories.

The information in short term memory is assessed by the brain according to whether it is important to us, it has strong emotional content, or it relates to something we already know. If the information passes these tests, it is passed into long term memory.

Long term memory

The brain uses two processes to put information into long term memory.

1. Encoding

The brain links all the relevant information together to form a memory, actually creating new synapses.

At this stage, the memory isn’t connected to other knowledge. Therefore we won’t have a good understanding of the concept, and we will find it difficult to recall, as it is isolated from the rest of our memory.

2. Consolidating or understanding

The new memory is linked to other information already in our memory. For example, a memory of a recent conversation may be linked to other memories about that person and other information on the same subject.

This means that we now have an understanding of the information, in terms of concepts and words that we already know and understand. We are also more able to recall the memory because it will come to mind when thinking about other associated information.

This consolidation process can take days if the information is new or complex, and may continue while we sleep. However consolidation can be stopped through fatigue and the information lost.

Recalling information

If we recall and use new information, more and more neural pathways are set up, linking it to a wider set of information. This makes it easier to recall and harder to forget, because there are many pathways to the information.

As we use our new understanding in various contexts, the pathways in the brain can be simplified and made more robust and efficient.

With repeated use over time, in different situations, the information will be so well connected in our brains that it will come to mind quickly and automatically when needed.

Thus, repetition, especially in different situations and contexts, is an important part of making information useful.

The brain continues to process the information it holds throughout our lives, setting up new pathways if it is used often, and abandoning pathways that are not used.

So why can’t I remember things?

We can see that there are several reasons why we may be unable to remember something we have heard or experienced:

- It may have been filtered out right at the start, because we were focusing on something else.

- Our short term memory may have become overloaded and the information was never passed into long term memory.

- We may not have used the information enough to strengthen the pathways, and it has become lost or difficult to recall.

- Our brains may not be working efficiently at the time because of tiredness or age.

Why is this relevant to churches?

Churches exist to make and grow disciples. Disciples need to learn (e.g. Biblical teachings) and apply what they know in their lives, so they mature and are transformed into active followers of Jesus.

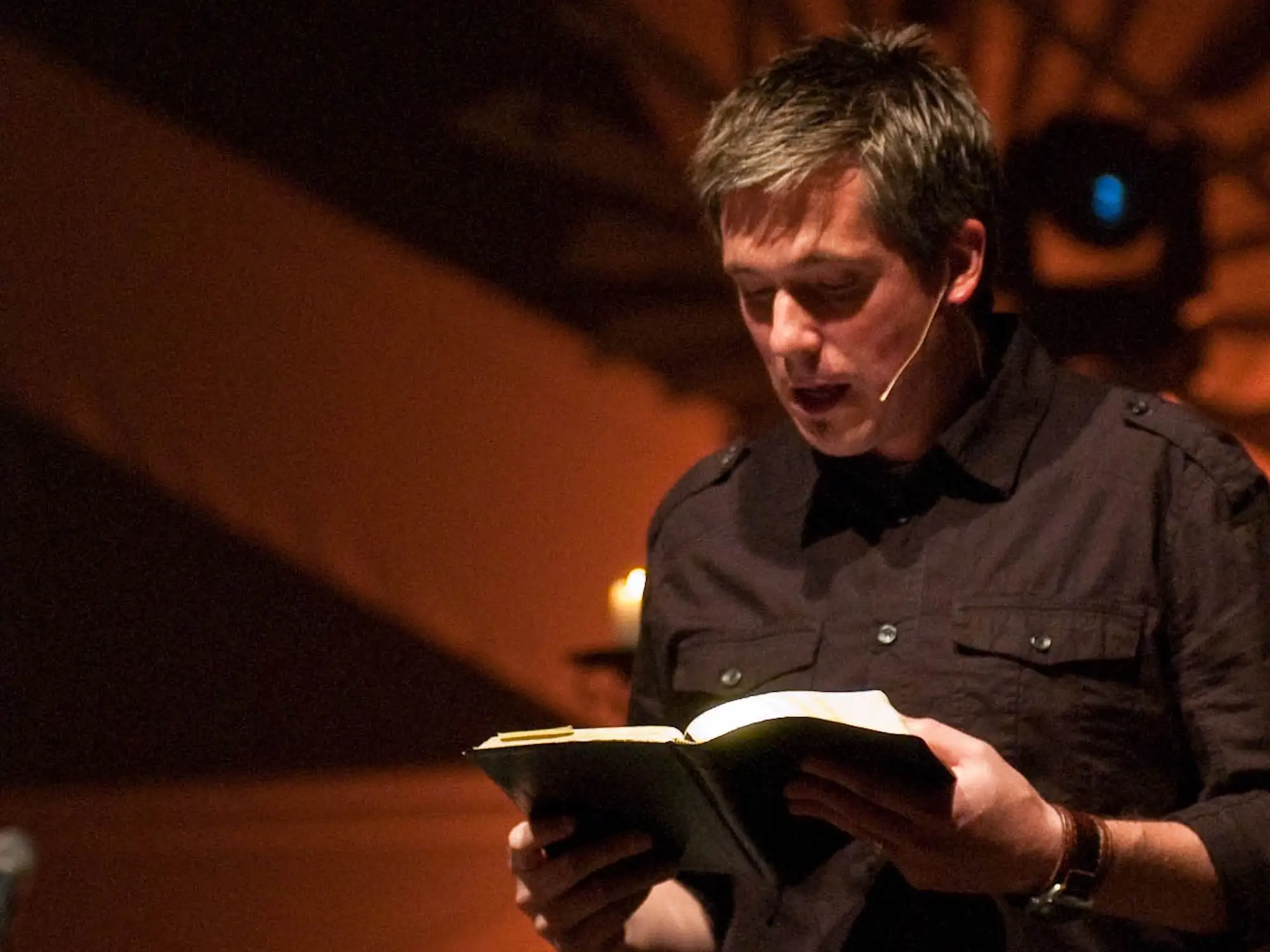

But for most churches, the main teaching method is sermons – long (20 minutes or more) monologues imparting information while the congregation sits passively listening (or not!).

But this doesn’t work well with our brains.

- Short term memory is generally overloaded after 10-15 minutes of information. After that, information will almost certainly be lost.

- Passive listening doesn’t help our brain process information. It is too easy to be thinking of something else and so information in the sermon is filtered out and we’ll be unable to recall much of what was said. To retain information, we need to be actively engaged and repeat what we are learning (to ourselves or someone else) and then use it in some way as soon as possible.

God’s way

God has chosen that we have brains that work as described here. We communicate and teach well if we work in harmony with how our brains are structured.

Active learning

Discussion, active learning and self-learning are important aspects of memory retention. There is much that could be done in churches to improve how the congregation learns and grows – see the links below.

Read more

Sermons: not a good way to teach and make disciples

All the scientific facts, with scores of references, about memory, learning and ways to do it better.

Discussion isn’t just a sharing of ignorance. Done well, it is an essential part of learning.

Lots of practical ways to promote active learning in churches.

Main photo by SHVETS production. Additional photo by Keira Burton. Diagrams are from Dr. Efrat Furst, and are used with her kind permission. Cartoon modified from an original by ASBO Jesus.

Leave a Reply